Transvaginal Mesh After Hysterectomy

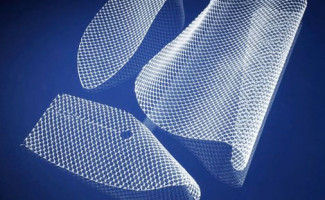

Transvaginal mesh may be used after a hysterectomy to address or prevent future occurrence of vaginal vault prolapse, where the upper portion of the vagina loses its shape and drops into the vaginal canal. This condition is more common following a hysterectomy, as the supportive structure of the uterus is no longer provided.

A surgeon will suture a mesh implant from the weakened portion of the upper vagina to surrounding connective tissues to offer more support. Surgical mesh may also be used treat weakened pelvic floor muscles, if a patient is likely to develop pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Historically, health care providers would implant vaginal mesh through an abdominal incision following a hysterectomy, but an increasing number of surgeons are inserting the mesh transvaginally, or directly through the vagina.

A surgeon will suture a mesh implant from the weakened portion of the upper vagina to surrounding connective tissues to offer more support. Surgical mesh may also be used treat weakened pelvic floor muscles, if a patient is likely to develop pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Historically, health care providers would implant vaginal mesh through an abdominal incision following a hysterectomy, but an increasing number of surgeons are inserting the mesh transvaginally, or directly through the vagina.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that hysterectomies are the second most common major surgery among women of childbearing age and an estimated 600,000 patients have the procedure each year. Patients who’ve undergone a hysterectomy are more prone to recurring pelvic organ prolapse, especially in cases where the operation was done to correct uterine prolapse.

Transvaginal mesh is frequently used to treat or correct problems with POP or vaginal vault prolapse after hysterectomies, despite the fact that thousands of women have suffered surgical mesh complications ranging from scarring, mesh erosion and compromise to internal organs.

Types of hysterectomy

Depending on the health of the patient and medical need for the hysterectomy, a surgeon may remove the entire uterus or only portions of the organ. A radical hysterectomy, which removes the uterus, cervix, ovaries, fallopian tubes and lymph nodes, is typically reserved for advanced cases of cancer. A total hysterectomy removes the uterus and cervix, and a partial hysterectomy, also known as a supracervical hysterectomy, removes the upper portion of the uterus, but leaves the ovaries and cervix intact – some studies suggest this may reduce the chances of POP and preserve sexual function.

Surgical procedures used to perform hysterectomies:

- Abdominal hysterectomy – A surgeon makes a five to seven-inch incision in the lower part of the abdomen. The incision may be horizontal near the bikini line, or may go up and down.

- Vaginal hysterectomy – The uterus is removed through a small incision placed inside the vagina. The surgeon may also opt to suture in transvaginal mesh to address any signs of POP.

- Laparoscopic hysterectomy – A laparoscopic instrument is used to make smaller incisions either in the lower abdomen or inside the vagina. The laparoscope’s tiny camera is used to guide the operation.

- Da vinci robot assisted hysterectomy – Using the mechanical arms of the Da Vinci robot, the surgeon performs an abdominal hysterectomy through much smaller incisions, purportedly resulting in less blood loss, fewer complications, and a shorter recovery period.

Why are hysterectomies performed?

A hysterectomy may be necessary for many different reasons, ranging from invasive cancers to chronic pelvic pain.

Some conditions that may require a hysterectomy include:

- Uterine prolapse

- Cancer of the ovaries, uterus or fallopian tubes

- Severe endometriosis, where the uterine lining begins to grow in the fallopian tubes, ovaries or other pelvic organs

- Benign uterine fibroids that cause bleeding, discomfort and other complications

- Abnormal or long-term menstrual bleeding

- Persistent pelvic pain

- Adenomyosis, or a thickening of the uterus

Mesh traditionally used to treat POP and SUI

Transvaginal mesh was introduced to the American public in the 1990’s as an effective treatment for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) – two very common conditions among women who’ve undergone a hysterectomy. What recipients didn’t know, however, was that mesh implants put patients at a higher risk for additional complications – some of them life-threatening. One of the most frequently cited problems linked to the devices is mesh erosion, also known as mesh extrusion, where the implant erodes through the tissue and adjacent organs, causing serious infection, pain, bleeding and damage to internal structures.

Other complications with vaginal mesh include neuromuscular problems, scarring, organ perforation, painful sexual intercourse, and emotional trauma.

One of the paradoxes of transvaginal mesh is that the devices often cause the conditions they are supposed to treat. In 2011, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned consumers that patients were reporting recurrent POP and incontinence after being implanted with vaginal mesh.

Surgical mesh complications following a hysterectomy

Escalating complaints of severe surgical mesh complications among women throughout the country prompted a safety communication by the FDA in July 2011. The agency had received more than 1,000 adverse event reports involving mesh implants by 2008, and determined that problems arising from the transvaginal placement of mesh were “not rare.”

The most common mesh complications reported to the FDA were:

- Mesh erosion or extrusion through the vagina

- Chronic pain

- Bleeding

- Infections

- Urinary problems

- Dyspareunia (pain during sexual intercourse)

- Organ perforation

The majority of these vaginal mesh problems required urgent medical intervention, subjecting women to revision surgery, surgical treatment, and hospitalization. The FDA concluded that in most cases, pelvic organ prolapse after a hysterectomy can be effectively treated without the use of surgical mesh, thereby avoiding any risks of potential complications. Additionally, federal regulators caution that vaginal mesh procedures have not shown any better outcomes when compared to non-mesh surgeries.

In the safety notice, the FDA urges health care providers to “advise [the] patient about the benefits and risks of non-surgical options, non-mesh surgery, surgical mesh placed abdominally and the likely success of these alternatives compared to transvaginal surgery with mesh.”

Resources

- National Institutes of Health, Risk of mesh extrusion and other mesh-related complications after laparoscopic sacral colpopexy with or without concurrent laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: experience of 402 patients. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18312989

- Da Vinci Surgery, da Vinci Hysterectomy, http://www.davincisurgery.com/da-vinci-gynecology/da-vinci-procedures/hysterectomy/

- FDA Safety Communication: UPDATE on Serious Complications Associated with Transvaginal Placement of Surgical Mesh for Pelvic Organ Prolapse, http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm262435.htm

- CTV News, More women seek surgery to relieve pain from transvaginal mesh, http://www.ctvnews.ca/health/more-women-seek-surgery-to-relieve-pain-from-transvaginal-mesh-1.1163700