Transvaginal Mesh

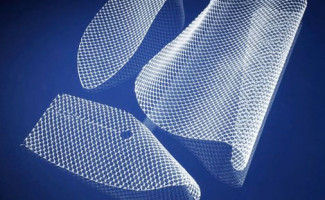

Vaginal mesh goes by several names, including transvaginal mesh, pelvic mesh, and surgical mesh. It is a synthetic mesh – similar to a woven sling or hammock – that is surgically implanted into the vaginal wall. Transvaginal mesh products were first introduced in the United States in 1996, and since have been marketed as a superior treatment for both pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI), conditions which were previously treated with corrective surgery.

Vaginal mesh goes by several names, including transvaginal mesh, pelvic mesh, and surgical mesh. It is a synthetic mesh – similar to a woven sling or hammock – that is surgically implanted into the vaginal wall. Transvaginal mesh products were first introduced in the United States in 1996, and since have been marketed as a superior treatment for both pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI), conditions which were previously treated with corrective surgery.

What is transvaginal mesh used for?

Vaginal mesh is most commonly prescribed for women who have experienced pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and/or stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Both conditions are more common in women who have experienced childbirth, had a hysterectomy, are in menopause, or are post-menopausal.

- Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP): In a woman with POP, the muscles in the vaginal wall (known as the vaginal floor) weaken, allowing her internal organs – the bladder, uterus, rectum, and other organs – to prolapse, or descend into the vagina. Vaginal mesh is meant to reinforce the vaginal wall muscles, so that the organs cannot prolapse.

- Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI): Stress urinary incontinence most often occurs after childbirth or in women with certain medical histories. Women with SUI have difficulty controlling their pelvic and sphincter muscles, which means that they may involuntarily urinate when under physical stress: running, jumping, laughing, etc. SUI is embarrassing, but is rarely dangerous.

Transvaginal mesh complications

Soon after the first mesh product approval in 1996, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began receiving complaints of serious complications and side effects from transvaginal mesh surgery.

Transvaginal mesh complications:

- Procedure failure: The patient is required to undergo additional surgeries

- Pelvic organ prolapse (POP): Recurrence of the condition

- Stress urinary incontinence (SUI): Recurrence of the condition

- Organ perforation: Surgical mesh can perforate, or puncture internal organs, including the bowel, bladder or blood vessels

- Mesh erosion or extrusion: The mesh can extrude, or push into the vagina or other organs, such as the urethra, bowel, bladder or rectum (known as rectocele)

- Severe pain: Often concentrated in the vagina, legs, pelvis or abdomen

- Chronic infection: Recurring infection around the mesh implant

- Mesh rejection: The body rejects the mesh implant, which will require additional surgeries

- Recurring urinary tract infections

- Vaginal scarring

- Chronic bleeding

- Urinary incontinence: This can occur even in patients who did not suffer incontinence prior to surgery

Revision surgery necessary to correct complications

By 2010, surgical mesh had gained significant ground as a popular treatment for POP and SUI. That year alone, more than 75,000 women were surgically implanted with transvaginal mesh products. Of those 75,000 women, 10%—at least 7,500 patients—reported vaginal mesh failure.

In addition to extremely uncomfortable side effects like vaginal scarring and organ perforation, many of these women were required to undergo painful, complicated transvaginal mesh revision surgeries. Vaginal mesh revision is more dangerous than the original procedure, since the vaginal tissue grows into and around the mesh. Removing the product is requires complex surgery and can result in tissue damage, pain, and other problems. During the lengthy recovery period, these women are also at a higher risk of infection.

FDA issues surgical mesh warnings, deems complications “not rare”

In 2008, the FDA informed the public that complications from transvaginal mesh were “an area of serious concern.” After conducting more research, the FDA updated their safety communication with serious warnings that vaginal mesh complications were “not rare.” Furthermore, the FDA warned, “It is not clear that transvaginal POP repair with mesh is more effective than traditional non-mesh repair… and it may expose patients to greater risk.”

In September 2011, the FDA’s Obstetrics & Gynecology Devices Advisory Committee met to review the risks associated with vaginal mesh. Though the committee declined to issue an across-the-board recall for all pelvic mesh products, they did establish new requirements for all new devices, including increased pre- and post-market data. The panel chose not to recommend the reclassification of vaginal mesh products from a Class II to Class III risk category, which “would require manufacturers to submit premarket approval applications, including relevant clinical data for these devices.” The reclassification was not implemented despite the fact that the majority of the committee members favored the change.

In January 2012, the FDA informed all vaginal mesh manufacturers that they must conduct three-year safety studies on their products.

Multiple vaginal mesh recalls issued since 1990s

In the 1990s, when vaginal mesh had just been introduced to the U.S. market, Boston Scientific Corporation issued the first surgical mesh recall. In question was the company’s ProteGen device, which had elicited thousands of complaints regarding safety concerns. In 2003, with little fanfare, Boston Scientific settled complaints from nearly 1,000 lawsuits.

Three years later, in 2006, Mentor Worldwide voluntarily took its ObTape mesh off the market. By July 2012, other companies followed suit. Johnson & Johnson, for example, suspended sales of four products in its Gynecare line: the Gynecare TVT Secur system, Gynecare Prosima, Gynecare Prolift and the Gynecare Prolift + M.

Manufacturers of transvaginal mesh

Numerous manufacturers of vaginal mesh products have been named as defendants in product liability lawsuits.

Vaginal mesh manufacturers and devices named in lawsuits:

- American Medical Systems (Endo Health Solutions): Elevate, Apogee, and Perigee

- Boston Scientific: Pinnacle and Uphold

- C.R. Bard, Inc.: Avaulta, Pelvisoft BioMesh, Pelvilace, Pelvitex, Pelivicol Acellular and Collagen Matrix

- Coloplast Corp.: Novasilk, Restorelle, Exair, Aris Transobturator Sling, Supris Suprapubic Sling, T-Sling with Centrasorb, Omnisure & Minitape Sling

- Cook Medical: Surgisis Biodesign Sling & Floor Graft, Stratasis Urethral Sling

- Caldera Medical: Ascend Anterior and Ascend Posterior

- Johnson & Johnson/Ethicon: Gynecare Prolift, Gynecare Prosima, Gynecare TVT

- Mentor Corp. (owned by Johnson & Johnson): Obtape Transobturator Sling

Vaginal mesh lawsuit information

Combine the prevalence of POP/SUI and the popularity of vaginal mesh, and add to it a high risk of complications (1 in 10 of all mesh recipients), and it’s easy to understand how transvaginal mesh lawsuits have flooded U.S. court dockets for more than 15 years. Many early lawsuits were tried or settled individually, but in recent years the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation (JPML) has consolidated these lawsuits into multidistrict litigation, or MDL.

Litigation is consolidated under one judge in the U.S. District for the Southern District of West Virginia:

- American Medical Systems, Inc. (Multidistrict Litigation No. 2325)

- Boston Scientific Corp. (Multidistrict Litigation No. 2326)

- Coloplast (Multidistrict Litigation No. 2387)

- C.R. Bard, Inc. (Multidistrict Litigation No. 2187)

- Cook Medical, Inc. (Multidistrict Litigation No. 2440)

- Ethicon, Inc. (Multidistrict Litigation No. 2327)

Additionally, complaints against Johnson & Johnson’s Mentor ObTape sling have been centralized in transvaginal mesh MDL litigation in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Georgia. Some plaintiffs in the J&J MDL have already reached out-of-court vaginal mesh settlements.

In a 2012 Bard Avaulta mesh lawsuit, a plaintiff was awarded $5.5 million in damages by a California state jury; in February 2013, plaintiff Linda Gross was awarded $11.1 million by a NJ jury, including $7.76 million in punitive damages, in a case against Johnson & Johnson over its Gynecare Prolift device.

In August 2013, the first transvaginal mesh MDL case to go to trial ended with a $2 million jury award for the plaintiff, who had filed suit against C.R. Bard for injuries sustained from the company’s Avaulta mesh product. Since that time, C.R. Bard has settled at least two more Avaulta cases for undisclosed sums before trial. With the total number of mesh lawsuits expected to exceed 50,000, news reports have indicated that large-scale settlement negotiations may be underway between attorneys representing mesh plaintiffs and at least five implant manufacturers.

Resources

- FDA Safety Communication: UPDATE on Serious Complications Associated with Transvaginal Placement of Surgical Mesh for Pelvic Organ Prolapse http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/safety/alertsandnotices/ucm262435.htm

- Urogynecologic Surgical Mesh Implants, http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/UroGynSurgicalMesh/default.htm

- New York Times, Women Sue Over Device to Stop Urine Leaks, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/05/health/05tape.html?pagewanted=all

- Bloomberg, Endo Health Unit Pays $55 Million in Vaginal Mesh Accord, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-06-21/endo-health-unit-pays-55-million-in-vaginal-mesh-accord.html

- Bloomberg, Bard, Vaginal-Mesh Makers, Said to Be in Settlement Talks, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-09-30/bard-vaginal-mesh-makers-said-to-be-in-settlement-talks.html

- MedPage Today, FDA Panel Wants More Data on Mesh Tx for Incontinence, http://www.medpagetoday.com/Washington-Watch/FDAGeneral/28444

- Bloomberg, J&J Owes $7.76 Million in Punitives in Vaginal Mesh Case, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-02-28/j-j-owes-7-76-million-in-punitives-in-vaginal-mesh-case.html

- United States District Court Southern District of West Virginia, MDL 2187 C. R. Bard, Inc., Pelvic Repair System Products Liability Litigation, Honorable Joseph R. Goodwin, http://www.wvsd.uscourts.gov/MDL/2187/